Drain the Oceans

How quickly would the ocean's drain if a circular portal 10 meters in radius leading into space was created at the bottom of Challenger Deep, the deepest spot in the ocean? How would the Earth change as the water is being drained?

–Ted M.

I want to get one thing out of the way first:

According to my rough calculations, if an aircraft carrier sank and got stuck against the drain, the pressure would easily be enough to fold it up[1] and suck it through. Cooool.

Just how far away is this portal? If we put it near the Earth, the ocean would just fall back down into the atmosphere. As it fell, it would heat up and turn to steam, which would condense and fall right back into the ocean as rain. The energy input into the atmosphere alone would also wreak all kinds of havoc with our climate, to say nothing of the huge clouds of high-altitude steam.

So let's put the ocean-dumping portal far away—say, on Mars. (In fact, I vote we put it directly above the Curiosity rover; that way, it will finally have incontrovertible evidence of liquid water on Mars's surface.)

What happens to the Earth?

Not much. It would actually take hundreds of thousands of years for the ocean to drain.

Even though the opening is wider than a basketball court, and the water is forced through at incredible speeds,[2] the oceans are huge. When you started, the water level would drop by less than a centimeter per day.

There wouldn't even be a cool whirlpool at the surface—the opening is too small and the ocean is too deep.[3] (It's the same reason you don't get a whirlpool in the bathtub until the water is more than halfway drained.)

But let's suppose we speed up the draining by opening more drains. (Remember to clean the whale filter every few days), so the water level starts to drop more quickly.

Let's take a look at how the map would change.

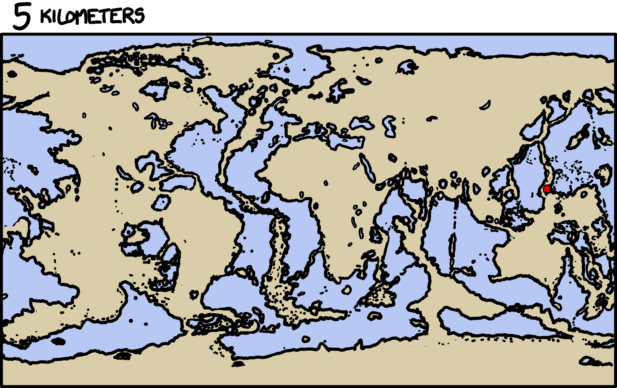

Here's how it looks at the start:

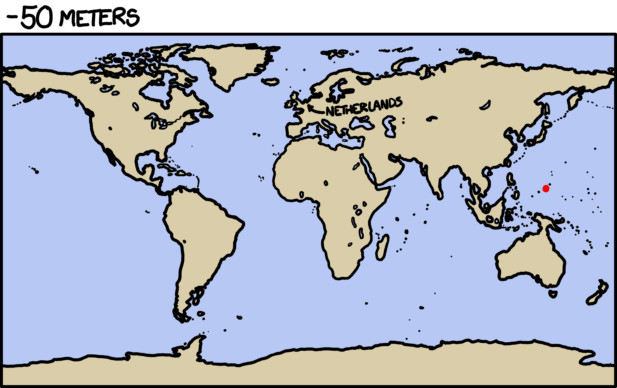

And here's the map after the oceans drop 50 meters:

It's pretty similar, but there are a few small changes. Sri Lanka, New Guinea, Great Britain, Java, and Borneo are now connected to their neighbors.

And after 2000 years of trying to hold back the sea, the Netherlands are finally high and dry. No longer living with the constant threat of a cataclysmic flood, they're free to turn their energies toward outward expansion. They immediately spread out and claim the newly-exposed land.

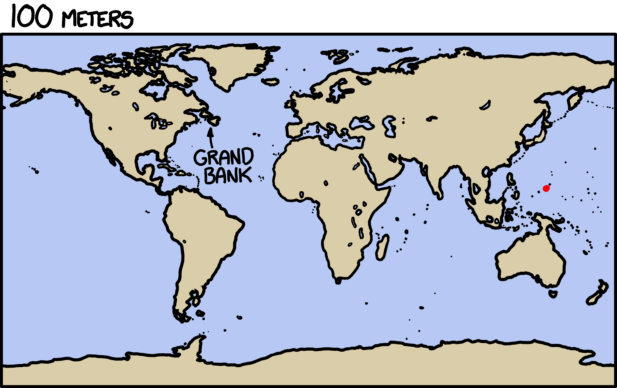

When the sea level reaches (minus) 100 meters, a huge new island off the coast of Nova Scotia is exposed—the former site of the Grand Banks.

You may start to notice something odd: Not all the seas are shrinking. The Black Sea, for example, shrinks only a little, then stops.

This is because these bodies are no longer connected to the ocean. As the water level falls, some basins cut off from the drain in the Pacific. Depending on the details of the sea floor, the flow of water out of the basin might carve a deeper channel, allowing it to continue to flow out. But most of them will eventually become landlocked and stop draining.

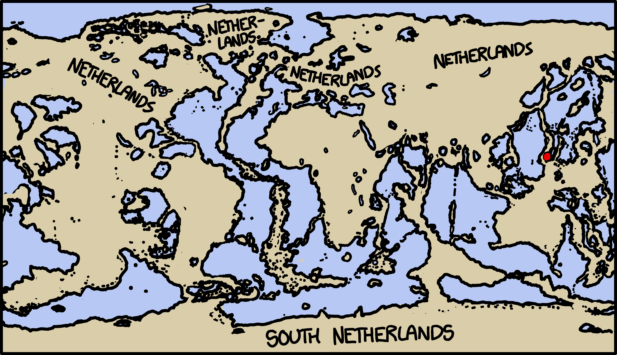

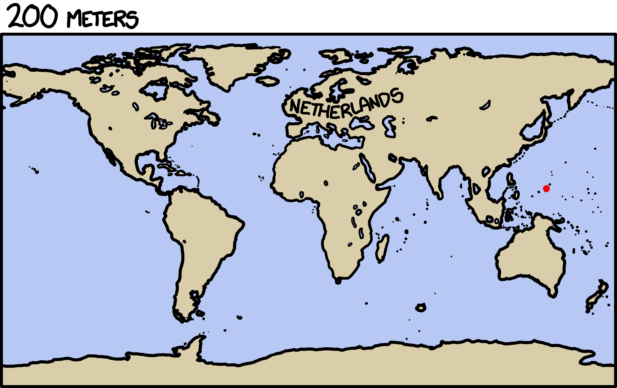

At 200 meters, the map is starting to look weird. New islands are appearing. Indonesia is a big blob. The Netherlands now control much of Europe.

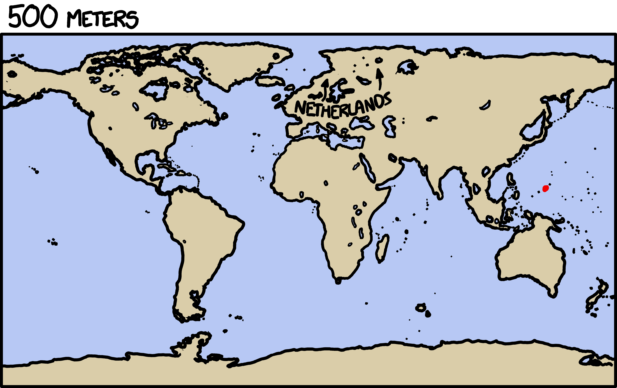

Japan is now an isthmus connecting the Korean peninsula with Russia. New Zealand gains new islands. The Netherlands expand north.

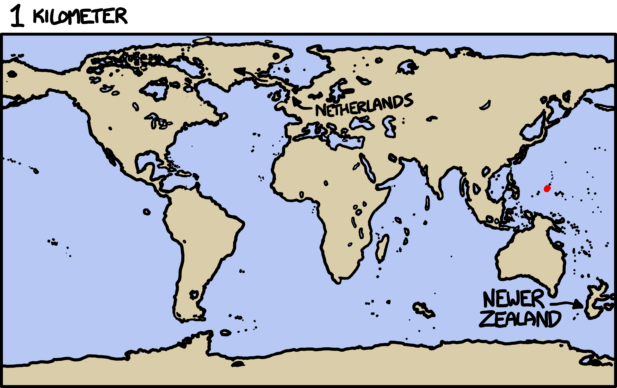

New Zealand grows dramatically. The Arctic Ocean is cut off and its the water level stops falling. The Netherlands cross the new land bridge into North America.

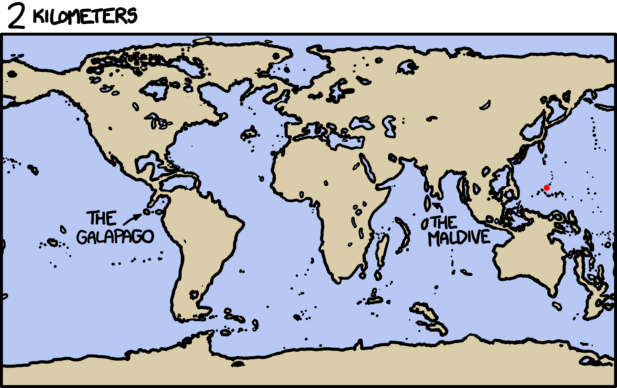

The sea has dropped by two kilometers. New islands are popping up left and right. The Caribbean Sea and the Gulf of Mexico are losing their connections with the Atlantic. I don't even know what New Zealand is doing.

At three kilometers, many of the peaks of the mid-ocean ridge—the world's longest mountain range—break the surface. Vast swaths of rugged new land emerge.

By this point, most of the major oceans have become disconnected and stopped draining. The exact locations and sizes of the various inland seas are hard to predict; this is only a rough estimate.

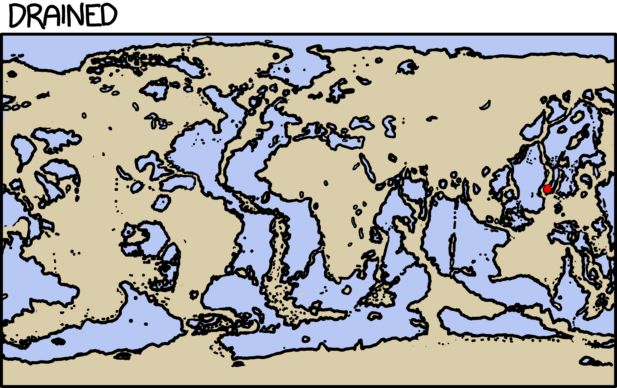

This is what the map looks like when the drain finally empties. There's a surprising amount of water left, although much of it consists of very shallow seas, with a few trenches where the water is as deep as four or five kilometers.

Vacuuming up half the oceans would massively alter the climate and ecosystems in ways that are hard to predict. At the very least, it would almost certainly involve a collapse of the biosphere and mass extinctions at every level.

But it's possible—if unlikely—that humans could manage to survive. If we did, we'd have this to look forward to: